By James Grossmann

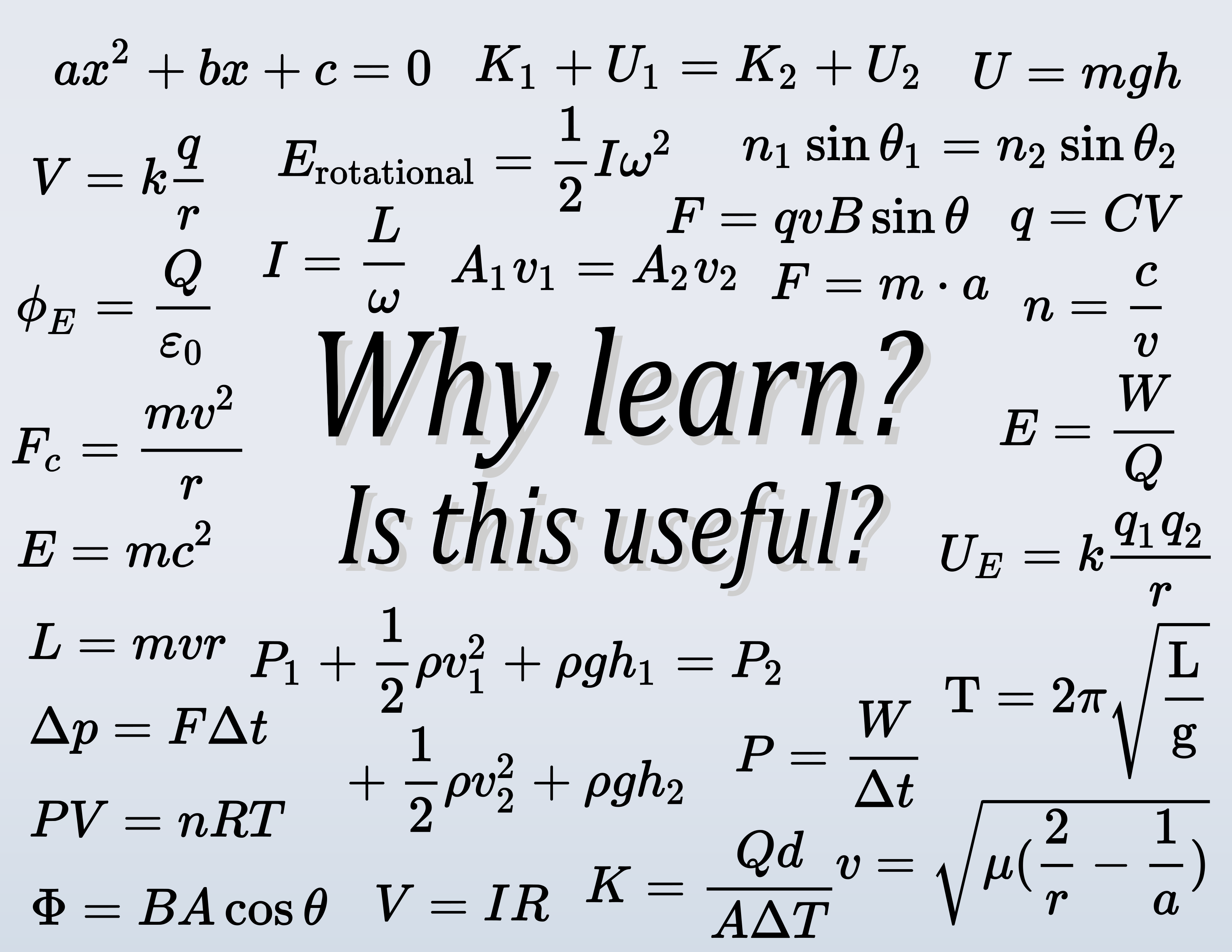

A quintessential criticism of secondary education that has persisted for scores of years is its supposed lack of application to the real world. Many high school students feel that the knowledge they learn in their classes will not be useful for careers and day-to-day life. In 2017, the nonprofit YouthTruth published results to a five-year-long, 230,000 student survey with results showing that less than of half secondary school students reported feeling “that what they’re learning in class helps them outside of school.” For high school students, the results were just 46 percent.

Since 2017, many events in the world – including the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent prevalence of misinformation that ensnares digital content – have demonstrated a need for society to maintain critical thinking skills more than ever before. In spite of this, many high school students do not see their education as being relevant to their later lives. “I believe the classes that I am currently enrolled in serve no purpose to my success in the future,” stated Colin Ray, a sophomore at Ponte Vedra High School (PVHS). “When will I need to know what Shakespeare really meant in Macbeth?”

David Jerome, a senior at PVHS, shared a similar sentiment. “Besides using some of the knowledge learned in my science and math classes in college, I don’t really see most of the skills I learned in high school being translated into life after school,” stated David. “Unless if you specialize in a specific field, you won’t use these skills day-to-day.”

To some end, there is merit to these statements. No, most students will not find themselves factoring trinomials or crafting literary arguments based on poetry as a daily part of their career. But studying subjects that are the most foreign to daily life – mathematics, biology, physics, chemistry, literature, and so on – open potential pathways that students can explore in college in addition to building skills tantamount to life in the modern era.

If a student wanted to be a marine biologist or an engineer or even just wanted to explore these potential career paths in college, they would be at a fundamental disadvantage had they not studied subjects in algebra and the basic sciences. In order to obtain an undergraduate degree in marine biology at the University of Florida, students must complete MAC 2311, a general education course in analytic geometry with basic differential and integral calculus. Completing this course would be an overwhelming assignment should students have opted to not have taken at least a second algebra course during their time in high school, potentially requiring two or three extra math courses before even being able to take the class. In this capacity, studying math opens opportunities and pathways in higher education. There are dozens of examples like this in all subject areas across hundreds of majors.

Beyond academia, however, many students simply feel that they are not learning critical skills to day-to-day life. “We don’t learn how to do taxes; we don’t learn how to do a mortgage; we don’t learn basic skills that are needed in day-to-day life,” David believes, a sentiment echoed by many students. “I think you learn stuff that is necessary for the classes, and it may occasionally lead into things you do day-to-day, but it’s generally not useful,” stated Braeden Wyman, a senior at PVHS. Braeden added that he wished he had learned “Simple mechanical stuff, like working with your hands. And cooking, it’s ridiculous that it isn’t taught.”

Sentiments like these are prevalent among high school students and alumni. In response to a 2,000-person survey commissioned by the Kauffman Foundation in 2019, 75 percent of adult respondents reported believing that a high school degree should teach students “skills needed to succeed in the real world,” a broad statement that encompasses skills from the aforemetioned taxes to crafting an email. But these notions imply that it is the inherent responsibility of the education system to teach these skills. Another argument, though, is that the obligation of teaching students these basic life skills would lie within parenting. Many would argue that the obligation of teaching a child how to file their taxes is a responsibility of the parents, much in the same vein as teaching a child how to tie their shoes. To that end, if students learn basic life skills from their parents or guardians, they can learn a variety of other multifaceted skills from their high school classes.

In many ways, the skills students learn in high school are of critical value to their future – both explicitly and implicitly. Of course, building writing skills in an English class or understanding how the U.S. political system functions through a government class are more obvious examples of basic skills that assist students in day-to-day life. However, the skills students take away from their high school classes are sometimes less obvious.

For Carter Holt, a chemistry teacher at PVHS, the skill his honors chemistry class teaches is self-advocacy. “Because the class is so hard, students have to learn to speak up and ask questions when they don’t understand the material,” stated Mr. Holt. Mr. Holt went further to compare students struggling in his class to future jobs they may hold, arguing that “In the corporate world, you’re expected to know how to do everything. Learning self-advocacy teaches you that it’s okay to ask questions and to stand up for yourself.”

Michele Meyer, a calculus teacher at PVHS, offered more examples of skills students learn in her class. “Mathematics is the class [where] you learn how to solve concrete and abstract problems. It teaches you to think on a higher level – to organize and interpret,” stated Mrs. Meyer. “Mathematics teaches you to be flexible with your thinking. A strong math class teaches you how to be patient and dive deeper to various ways/methods to problem solve – to persevere.”

“Mathematics… teaches you to think on a higher level.”

Ms. Michele Meyer

Mrs. Meyer also stressed that math classes stress “collaboration,” teaching students how to “build off previous knowledge and work with people,” how to “build relationships,” and “To be able to not only solve a problem but to communicate it to others.” “In this ever-changing world we need people who understand and who can apply mathematics,” Mrs. Meyer argued. Mrs. Meyer believes that these traits are needed for any path of study students wish to pursue.

There are thousands of examples of these minutiae that assist students in their day-to-day lives. Exposing students to world history and forms of literature indirectly teaches them how to critically think about contemporary world events. Studying English in general is the act of learning to read and comprehend – a skill that is fundamental to living in the modern, digital world and a skill many students will not understand the value of until they come to use it in their day-to-day life. Courses such as physics and chemistry teach students quantitative reasoning skills, teaching students how to analyze graphs and equations in order to understand how variables are functionally related to one another – a skill that goes beyond the classroom and into any chart or graph the students may encounter in their jobs or just while reading the news. While students will most certainly not learn about filing taxes, investing, or filling out W-2 forms in their economics class, the concepts students learn in economics will translate into understanding these concepts as students encounter them in the real world. Students who have taken statistics and hold a basic understanding of confidence intervals, significance tests, and the idea of a p-value will enjoy being able to easily interpret whether an academic or medical article contains helpful data while conducting formal research in college, careers, and beyond. Subjects such as algebra and calculus teach problem solving skills that teach students to reevaluate scenarios in order to determine a process to arrive at a result, a school of thought that applies to a plethora of disciplines. Despite these subjects being so different, they all foster skills that will resonate within students for years to come.

Madeleine Herwit, a senior at PVHS, ultimately came to this conclusion, which is part of why she intends to major in Aerospace Engineering before going to law school. “As someone who would like to major in engineering and pursue a career in law, the ability to think, read, and write will be of the utmost importance in my success,” stated Madeleine in reference to her classes at PVHS. “I would have to be silly to say that I do not [use these skills in day-to-day life].”

Madeleine appreciates a wide variety of skills from all of her classes, but she has found that “The most valuable skill that I’ve learned in my classes at PVHS is without a doubt critical thinking.” Madeleine posits that “It is a skill found in so many classes from English to math that is so necessary to be successful.” In this rapidly evolving digital era where information is available with just a few taps, the ability to critically think about information from a variety of sources is a necessity for a society to avoid political and social dysfunction. Critical thinking comes from many sources, but the most fundamental source of critical thinking is education.

“In English, critical thinking is imperative to write well and something that I’ve gotten quite good at through the years. However, it translates to so many other classes,” Madeleine believes. “In calculus, not every question is straightforward and may require multiple elements of different units to solve a single problem, and of course it is those critical thinking skills that allow for one to understand what goes into each problem. While I may not ever need to calculate the temperature of milk at time t = 2 seconds using differentiation again, it is the ability to think in a way that gets the solution that is of value to students.”

“The skills I’ve learned in high school have only made me more confident in my ability to think.”

madeleine Herwit

Madeleine believes that “In a classroom I won’t be taught how to solve every issue I’ll ever come across in the real world because that would stunt innovation and progress.” Instead, she argues “It is the ability to think that keeps society moving forward with new ideas and creations.”

In any capacity, outside of any benefits to education, knowledge for the sake of knowledge may never be a bad thing. Exposing students to a variety of interdisciplinary areas of thought sharpens their ability to think and may just introduce them to a new interest. Colin, who so thoroughly believes “English is a prime example” of a class of little value to his future, has come to believe that “biology serves a purpose because it teaches us about life and how it works.” For Madeleine, she believes “The skills I’ve learned in high school have only made me more confident in my ability to think,” an ability she employs in many ways, from analyzing “the persuasive techniques politicians use” to “leisurely time reading at home,” for “If one simply reads the words on the page and doesn’t ponder on their meaning, the book becomes devoid of all purpose. I could never really understand what I read if I didn’t learn how to read back in AP Lang — and what is reading if not thinking?”

The idea of neuroplasticity – a neuroscience concept that relates to the ability of the brain to form new neural connections and strengthen existing ones, ultimately allowing the brain to perform new functions as neuroplasticity increases – is directly correlated with education. As a student learns, their brain is learning too – quite literally forming new connections and learning how to think in new ways. When a student learns how to solve a math problem, their brain is being conditioned to problem solve and critically think in new ways. When a student analyzes a poem for specific literary elements, their brain is learning how to scan texts of all kinds for all sorts of different qualities. When a student learns, their brain learns to think in new ways.

To that end, learning just for the sake of learning is emphatically justified – especially when the most critical point of brain development may be during the secondary education age range. Even in a course where, as Madeleine describes it, “the only way to pass is to know specific terms, it has been the ability to sit and study such terms for hours at a time that may be picked up [by students].” Learning anything teaches students how to study, how to manage their time, and how to be flexible in response to challenge – vital skills in day-to-day life. Being exposed to a variety of different subjects – especially those that feel foreign and challenging – pushes students to become better learners, a skill that is tantamount to success in college, careers, and life. Because of this, Madeleine believes that “there could never exist a course that has no benefit in any way, shape, or form.”